Should some historically important books still be in print today? Where does the freedom to publish begin and end?

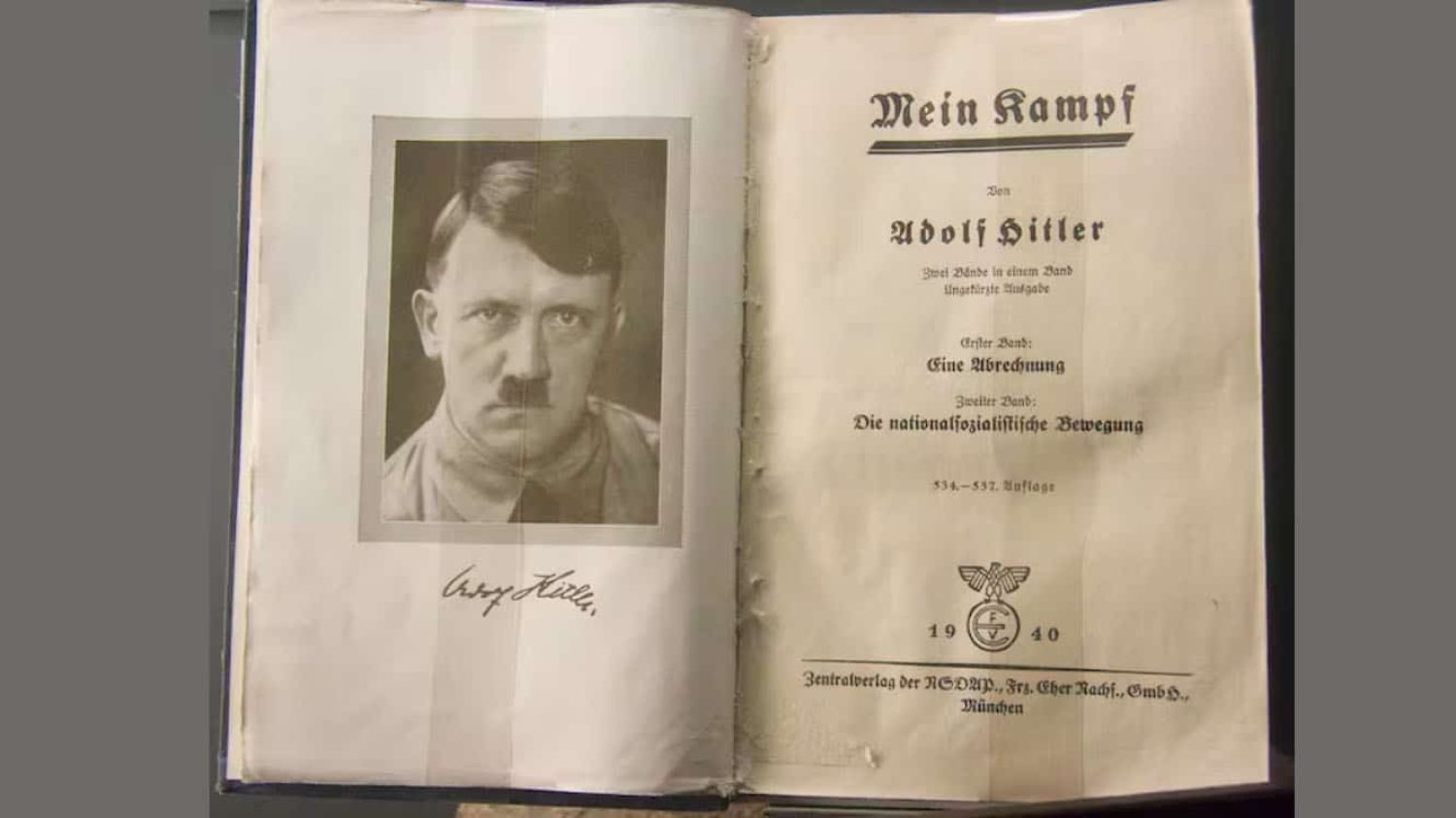

Hitler’s Mein Kampf was first published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, in a hardback edition with a swastika on the spine. It sold poorly and was found by most readers to be a turgid read. It was only with Hitler’s rise to power that the book became a bestseller, available in various formats to target different markets (eg, there was a knapsack version, designed for serving soldiers). The book became the Nazi Bible and every ‘good’ German was expected to buy a copy. Interestingly the style of Gothic lettering called Fraktur which appeared on the early editions was found in 1941 to have been invented by a Jewish man, so that was changed. It is thought that 12 million copies of the book circulated in Germany, although many were paid for by the state. A few abridged and translated versions were sold outside of Germany – by 1939 the book had been translated into fifteen languages. An expurgated translation was even sold in England in a serial format during the war, with royalties going to the Red Cross.

After Hitler’s death, the copyright of his book passed from his estate to the Bavarian State Ministry of Finance. While the swastika was banned in post-war Germany, there was no ban on the book whose ideology had caused the Holocaust. But the holders of the copyright chose not to reprint the book. When that copyright expired in 2016 a critical edition was planned, with notes, explanations, and corrections of Hitler’s wrong assertions included. It was published in two large volumes that extend to nearly 2000 pages.

And yet creating a critical edition such as this one confers on the book a status it does not deserve. Does it dignify his lethal racism by presenting it in an authoritatively historical way? How to present Hitler’s book raises many ethical and commercial issues.

A right-wing publisher Der Schelm also published the book, in a cheap edition with no added commentary, insisting that publishing the book was an individual freedom. Amazon banned it in 2020, then retracted the ban, and the publicity connected with that banning lifted sales (it has proved extremely popular in India with right-wing Hindus who see it as a textbook in strong leadership).

How should this ghastly book be handled? Should it be available to readers on library shelves, or in bookshops? Where should the publishing profits go? No one can argue that it is not historically important. As a work of literature, it is negligible – Hitler was no prose stylist! But as a book that shaped our modern world, perhaps it should be available? I hate the banning of books, but can see that there is a case for banning this one.

What do you think? Should this book which changed the world and caused millions of deaths be ‘out there’? Or do we decide that history cannot be whitewashed or forgotten and that Hitler’s obscene words should be available to all? Tell me by leaving a comment.

Note: The above information came from Emma Smith’s excellent book Portable Magic: A History of Books and their Readers, published in 2022.

Comments are moderated, and will not appear until approved.

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_PLUS]

Susannah Fullerton

Happy New Year, John. I hope it is full of good books.

I agree with you about Mein Kampf, though am not sure I will ever read it myself. It is an important book when it comes to history and the impact it had, so I don’t thik it should be banned. And banning it must now be pretty pointless, as anyone who wants it could find it on the web.

John Power

Personally, I read Mein Kampf many years ago and am glad that I read it: I think it is important to read key, original, historical texts as best one can (I cannot read German, so had to read an English translation), in order to understand history; and I accept the oft-cited claim that knowledge of history helps us not to repeat it. The reading of history can certainly help to inform current decisions, and there is value in reading it as directly as is practical, rather than relying upon the accuracy of accounts about it.

So I think such books should not be banned. Perhaps restrictions on their availability might be sensible, but it is hard to imagine restrictions being practical in this technological age. Even if a book was banned in Australia, a quick internet search should be able to find it.

So, at least at present, I would oppose a ban on a book such as Mein Kampf.

Graham

Well that’s a controversial start to 2023! It’s not the worst book I’ve ever read, and its author makes a lot of insightful points. I don’t think it breaches any principles that would not also disallow, say, The Bible, or George Bernard Shaw’s “Heartbreak House”, or William Butler Yeats’ “Under Ben Bulben”, or Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness”. Or the American Declaration of Independence for that matter, with its gripes about “merciless Indian Savages”. And what about the Treaty of Versailles, where Australia successfully argued that the Japanese were less than fully human – do you still publish that historical Australian contention today? or not?

It’s customary to draw the line between “acceptable” and “unacceptable” as you transition from “advocating” an illegal action (which is OK) to “inciting” an illegal action (which is not OK). But even that’s only true within a national jurisdiction. In the lawless frontiers of the Internet, or of global politics, Mein Kampf is only a mouse-click away on Project Gutenberg, and there’s no higher authority to adjudicate on that. There’s also no requirement that says you have to believe the bits of Mein Kampf that are false – and as for the bits of it that are true, banning the whole book or constraining it to non-scholarly editions won’t make them any less true. Just switch your critical faculties on before you read it would be my advice. I can’t think of any book that I’ve ever read that I believe to be completely true, or completely false.

Susannah Fullerton

I wanted to get everyone thinking about the issue, so am glad you felt stirred up by it.

Yes, the book is easy to find on-line, so banning it is really pointless. Nor do we have to believe what is in it, and most of us have the knowledge to recognise when Hitler is just mindlessly ranting.

I can, however, think of a book that is cpompletely true – JA’s ‘Emma’. It is so utterly true to human nature, so true in exactly the right choice of word, so true in its understanding of the world.

I am curious as to why Yeats’s Under Ben Bulben was on your list amongst Conrad, Shaw and the Bible??

It can be argued that the Bible is a book that has caused far more harm than Mein Kampf – religious wars, intolerance, discrimination etc. I guess it depens on whether you regard it as fact or, as in my view, fiction?

Anyway, lots to hink about and ponder. Happy New Year!

Graham

Probably too huge a topic to squish into a Blog, “Curious”, but to answer your question:

Firstly, Yeats’ “Under Ben Bulben” is about the centrality of violence to the human condition, and the nexus between violence and wisdom. It’s integrated. In that poem, the saintly St Michael prays for war, and even the “wisest man” is gripped by violence. There are similar exhortations in the Conrad, and the Shaw, and many other western writers. William Blake comes to mind: “The tigers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”. It’s not light years away from the thinking in Mein Kampf: “The soil on which we now live was not a gift bestowed by Heaven on our forefathers. But they had to conquer it by risking their lives.”

Secondly, western liberal democracies, far from having a mature, integrated view of violence, hold a disjoint view of violence. On the one hand they endlessly binge-watch a celluloid world of Netflix movies rated “strong violence”, “strong horror” and “strong gore”. But simultaneously, and without any sense of irony, they recoil aghast at actual domestic violence, at workplace bullying, and at teachers clipping wayward schoolchildren around the ears. It would nowadays be regarded as unacceptable to channel the cast of Lionel Bart’s “Oliver”, and to assert that “it’s wise to be handy wiv a rolling pin / Wen the landlord comes to call”. The unity of violence and wisdom is stridently denied by our society.

Thirdly, the Bible cannot possibly be true. It gives the value of pi as “three” (1 Kings 7:23), which would mean that all circles would be hexagons. But in any case, I would dispute your dichotomy between “fact” and “fiction”. Myths, and the Bible, and for that matter “Emma”, are both fact, and fiction, and neither.

Which, fourthly, brings us to the unalloyed “truth”, or otherwise, of “Emma”. Following the lead of French economist Thomas Piketty, the phrase “Jane Austen world” is very widely used as a pejorative term in today’s society and in popular debate. “Emma” world is unequal and unfair (according to Piketty), and the heroes are undeservingly rich and patrilinear, and they don’t pay their fair share of death taxes. Mr “Knightley” (on that view) is “false”, not “true”. “Knights”, for modern progressive liberals, are far from being swoon-worthy, and are an undesirable violent oppressive medieval anachronism. The kinda people whose forebears, in the words of “Mein Kampf”, “conquered the soil on which they now live, by risking their lives”. Putting all that another way – if “Emma” is “true”, then “Mein Kampf” is also, “true”.

Susannah Fullerton

Gosh, a lot to think about – I’m going to have to ponder the ‘true/false’ discussion more carefully. I clearly need to go back and read Yeats’ Ben Bulben as your analysis was interesting and I certainly agree about violence in today’s world – so acceptable on TV and in games, but unacceptable elsewhere, but so little connection drawn between the two.