Authors use pen names for a variety of reasons. They may wish to hide their identity or their gender, they may wish to have a different name for another style of book they choose to write, they may already be famous and want to test publishers or the market with a new book that is not under their usual name, or they may simply feel their own name is too prosaic or dull. In 2022/23 an exhibition on pen names was held at the National Library of Scotland. I’d have loved to have seen it, but couldn’t. However, there is now a book based on the exhibition which I have greatly enjoyed reading.

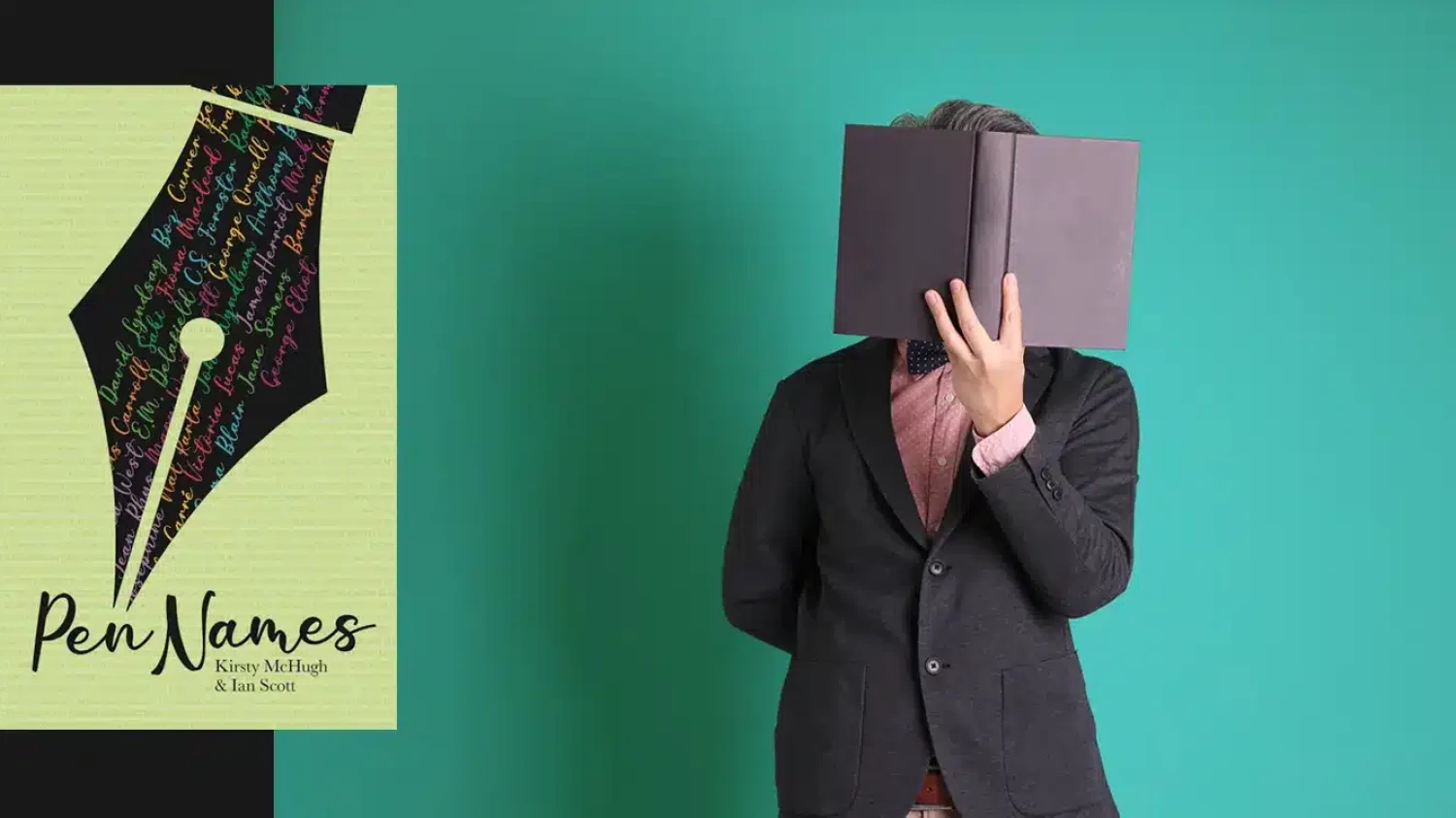

Pen Names by Kirsty McHugh and Ian Scott, published this year, was written by two of the curators of that exhibition. It discusses forty authors, explaining why they chose pen names and how they came to make that particular choice of name, showing how it sometimes got them into trouble, how successful they were in hiding behind these names (Elena Ferrante is probably the most successful so far), and much more.

Some of the authors chosen were very familiar to me. I knew all about Mary Anne Evans turning herself into George Eliot, and that Agatha Christie published non-crime fiction under the name of Mary Westmacott. Currer Bell for Charlotte Brontë, George Orwell for Eric Blair, James Herriot for Alf Wight and Robert Galbraith for Joanne Rowling were all pen names where I knew the background story. But I still found so much to learn in this beautifully presented little book.

Did you know that bestselling Lee Child is really James Grant and that his pseudonym originated from a family joke? Evidently he did research which showed that 63% of bestselling authors’ names began with the letter C. I was intrigued to read about Rahila Khan who was actually an English vicar called Toby Forward. His book was about young British Asian women and the agent and publishers all believed that the author was also young, female and Asian. When they found out, copies of his book Down the Road, Worlds Away were pulped. All this raises questions about authenticity in literature – does a writer have to share the background of his or her characters? Anthony Burgess, who was really John Wilson worked for the Colonial Service in Malaya and was not allowed to use his own name on a novel. But I did not know that he also published under the name Joseph Kell and, as Kell, he reviewed an Anthony Burgess novel for The Yorkshire Post, and was sacked for doing so.

This book is packed with fascinating stories. I learned more about Frank Richards (author of the Billy Bunter books), how Nicci French (a husband-and-wife team) manage to compose their crime novels, M.C. Beaton (Marion Chesney) who has written 160 books, and C.S. Forester, P.L. Travers, John le Carré (David Cornwell) and Saki.

When my book is published later this year, I won’t be hiding behind any pen name. I’d like to see my name blazoned in lights in Times Square and on the Sydney Opera House, and will gaze at my own name on the cover with pride. Yet Pen Names made me see that not every author feels as I do. I can really recommend this book.

Do you know of other authors who use pen names? Please let me know your thoughts in a comment.

Selected links for relevant websites, books, movies, videos, and more. Some of these links lead to protected content on this website, learn more about that here.

Vanessa Coldwell

Josephine Tey was really called Elizabeth MacKintosh.

Heather Grant

Ruth Rendall wrote thriller novels under the name of Barbara Vine. I’m very sure there are many more.

Jane Butterworth

Henry Handel Richardson was Ethel Florence Lindsay Richardson

Susannah Fullerton

Yes, indeed. I think she was frightened to publish her brave books under her own name.