In 1817 the British Museum announced that soon it would have on display a massive head of the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramesses II. The carved head of the Pharaoh had been removed from his tomb at Thebes by an Italian adventurer. The statue did not actually arrive in Britain until 1821, but the mere news of its coming was enough to inspire Percy Bysshe Shelley. He suggested to his friend Horace Smith that each of them write a poem about this piece of antiquity.

Smith’s sonnet Ozymandias (which is the Greek name for Ramesses) was published soon after Shelley’s poem. Shelley’s effort is now known as one of the great poems of all time, while Smith’s is almost never heard of. Smith did a perfectly competent job with his poem. Shelley, however, took his poem into the realm of sheer magic.

I’m giving you both of them, so you can compare:

Shelley’s Ozymandias

I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: “Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.”

Smith’s Ozymandias

In Egypt’s sandy silence, all alone,

Stands a gigantic Leg, which far off throws

The only shadow that the Desert knows:—

“I am great OZYMANDIAS,” saith the stone,

“The King of Kings; this mighty City shows

“The wonders of my hand.”— The City’s gone,—

Nought but the Leg remaining to disclose

The site of this forgotten Babylon.

We wonder,—and some Hunter may express

Wonder like ours, when thro’ the wilderness

Where London stood, holding the Wolf in chace,

He meets some fragment huge, and stops to guess

What powerful but unrecorded race

Once dwelt in that annihilated place.

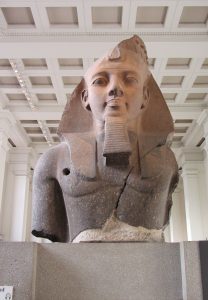

Ozymandias, the statue whose imminent arrival inspired both poems.

This is the statue whose imminent arrival inspired both poems Shelley’s wonderful sonnet is about power and its ultimate futility. Shelley loathed the idea of authority. He hated the church, the government (look at his fabulous poem The Mask of Anarchy to see what he thought of the politicians of the day), the army, and religion (he was expelled from Oxford University for atheism). In the poem, the shattered face of the once-tyrant ruler stands in a desert wasteland. The ruler’s boast of ‘Look on my works, ye mighty and despair’ is ironically disproved. His works have crumbled, his civilisation has disappeared – time has turned it all to dust. Now the statue is only a monument to the overweening pride of one individual. Readers are made to feel the insignificance of the individual when it comes to the passage of history. We hear about this statue from someone who has met a traveller who has seen it, so we are immediately put at a remove from the statue and the power Ozymandias once represented. He is made less commanding by this narrative device. And yet, one thing does remain – and that is a work of art, the statue. Shelley makes his readers aware of the power of art – when power, tyranny and politics are gone, the richness of language, poetry and art endure.

I was intrigued on a visit to Egypt to be told by several guides that Shelley had been to Egypt and had seen there a statue of Ramesses II. I tried to contradict this fable, as Shelley never got to Egypt, but I suspect the guides continued to give that story to unsuspecting tourists. Why spoil a good story with the truth? But their embroidering of the truth is a testament to the power of a good poem – Shelley’s poem is universal in its themes, imagery and language.

Share your thoughts by leaving a comment.

Selected links for relevant websites, books, movies, videos, and more. Some of these links lead to protected content on this website, learn more about that here.