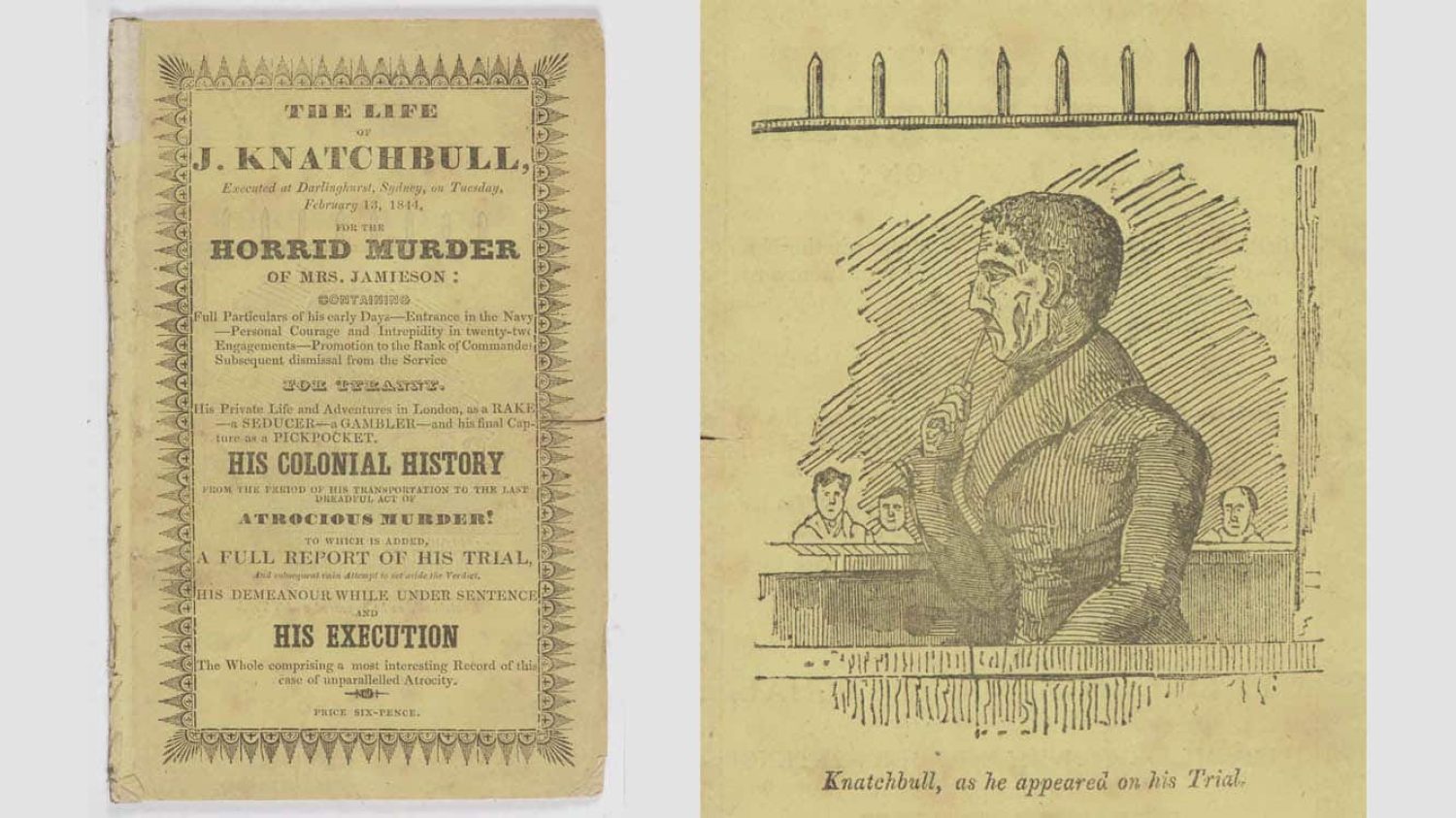

John Knatchbull’s case tested ideas of insanity for the first time in an Australian court. In a one-day trial on 24 January 1844, it was argued that insanity of the will could exist quite separately from insanity of the intellect, and that Knatchbull had yielded to an irresistible impulse. In short, he could not be held responsible for his crime. The members of the jury were not having any of that, and the jury returned a verdict of guilty without even leaving the box. [1]

On the hot Australian summer morning of 13 February 1844, a man was led forth, closely guarded, from the impressive gates of Darlinghurst Gaol in Sydney. It was 9 o’clock in the morning, but already 10,000 people had gathered in the public square in front of the prison, eager to watch the last moments of the condemned man. He was praying as he walked and “appeared to be deeply sensible of the awful position in which he stood. A dark and frowning eternity began to press itself with fearful force upon his mind, while his apparently sincere cries for mercy became more and more earnest as the tragic scene drew on.” He was given a chance to speak some last words to the two clergymen who were present, and then he mounted the scaffold. The noose was placed around his neck, and the man “was launched into another world”. Church bells tolled his passing nearby. The huge crowd, which included women and children, watched silently, awed by the solemnity of the spectacle and, after the body was cut down and removed to within the prison, they quietly walked away. The event was widely reported the next day in Sydney newspapers, so those who had been unable to attend, could read all about it there.

What possible connection could there be between this man, and the great novelist Jane Austen who had died more than 25 years before this horrid event? John Knatchbull was the half-brother of Edward Knatchbull who married Jane Austen’s favourite niece Fanny Austen Knight. Edward and John’s father, Sir Edward Knatchbull, had twenty children by his three different wives. Fanny’s family and the Knatchbull family, also from Kent, had known each other for some years before her marriage with Edward united them, and it is quite possible that Jane could have heard something of the ‘difficult’ son of the family.

John Knatchbull was probably born in 1793 (he was baptized in January of that year) in Kent. As a schoolboy he displayed “vicious inclinations” and when he joined the Navy, he soon found himself treated with contempt by fellow officers, and in financial difficulties. To pay what he owed, he indulged in petty frauds and in 1824 he was tried for the theft of two sovereigns and a blank cheque form. That was enough in value to see him hanged in England, but the judge was lenient on the young man and instead sent him to Botany Bay, the dumping ground for England’s unwanted criminals. John Knatchbull was sentenced to remain in Australia for 14 years before being permitted to return to England. His Kentish family was relieved to be rid of him.

The family black sheep failed to behave any better once he was in Australia. In 1831 he was sentenced to death for forgery. But once more the sentence was commuted, this time to seven years of penal servitude on Norfolk Island, about the grimmest place a convict could be sent.

In his time on Norfolk Island John took part in two mutinies and tried to poison with arsenic the food prepared for the guards. However, by 1839 he was back in Sydney. In 1844 John Knatchbull was planning to marry, but he needed money. Returning to his brutal ways, he stole from a shopkeeper Ellen Jamieson, then killed her by hacking at her skull with a tomahawk. Her two children were left orphaned and her murderer was described by the judge as “a wretch of the most abominable description”. This time there was no leniency and John Knatchbull was sentenced to hang. Darlinghurst Gaol is still there today (though an art college, not a prison, now does business behind its high stone walls). The square where the 1844 hanging occurred is named Green Square, not for the colour of the grass that grows there but because Mr Green was the name of the hangman.

Had Jane Austen still been alive, no doubt she and Fanny would have discussed the shameful story and its horrific outcome. Both women were aware that another member of their family could also have ended up in the Antipodes. Aunt Jane Leigh Perrot had been at serious risk of a trip to Botany Bay, when she was accused of shoplifting in Bath in 1799. Incarcerated for some months in Ilchester Gaol, Mrs Leigh Perrot had defended herself vigorously and, at her trial, she was acquitted. However, she knew a journey to Australia was highly probable and made plans that her husband James would accompany her if she was sent there. The entire Austen family must, at this worrying time, have speculated about what life in the colony would be like for their relations.

Jane Austen was interested in prisons. In 1813 she visited Canterbury Gaol with her brother Edward, who had to visit the institution as part of his duties as a magistrate. This was a most unusual thing for a Regency lady to do. My book Jane Austen and Crime explains what sort of institution she saw there. Jane Austen’s interest in punishment and imprisonment went into her next novel, Mansfield Park, a novel that is rich in prison imagery and a book that examines various types of imprisonment in its themes.

Susannah Fullerton: Lots of Jane Austen links

Susannah Fullerton: Austen’s Crime & Punishment

Susannah Fullerton: Jane Austen and Crime

State Library of NSW: A huge crowd for a hanging: the end of John Knatchbull

Australian Dictionary of Biography: John Knatchbull (1792–1844)

Jane Austen Centre: Fanny Austen Knight (Knatchbull)